By Courtney Knerr, Social Media Specialist and Molly Jenkins, Senior Writer

“Without a doubt, dogs will pick up on me feeling tense, which is not uncommon when evaluating the behavior of animals new to the shelter,” said Ben Shumway, Adoptions Associate at the Dumb Friends League. “They’re taking cues from me all the time, so if I’m concerned, the dog will be too.”

In Ben’s 15+ years with the League, he has become quite attuned to how his behaviors and emotional state impact those of the animals he works with. Dogs, who have co-evolved with humans over many thousands of years, are often particularly sensitive to people’s behavioral cues, gestures, and even subtle changes in facial expression. Likewise, recent research suggests that we also depend on the behavior of our animal companions to gauge whether an environment or situation is safe.

Over time, Ben has gained valuable experience in introducing dogs to other dogs – a delicate dance where the handler plays a larger role than one might expect. At the League, dogs in our care often engage in supervised visits with patrons’ dogs as part of the adoption process, but we also test dogs to see how they respond to each other before placing them on the adoption floor. This information not only helps us match dogs with the right adopters, but also supports their individual needs during their shelter stay.

That said, it is important to note that this information is largely contextual. After all, the shelter is an atypical and stressful place, with many animals coming in as strays or from unsafe living situations. They are confused, scared, in grief, and have no idea what is expected of them or what lies ahead. Ben often makes an analogy to first dates or job interviews when explaining how uncertain dogs can feel during these initial canine meetups. “Think back to a first date you’ve had,” he says. “How did you behave? I know that I behave in ways I normally wouldn’t when I’m anxious or not confident. Same with dogs, especially in the shelter.”

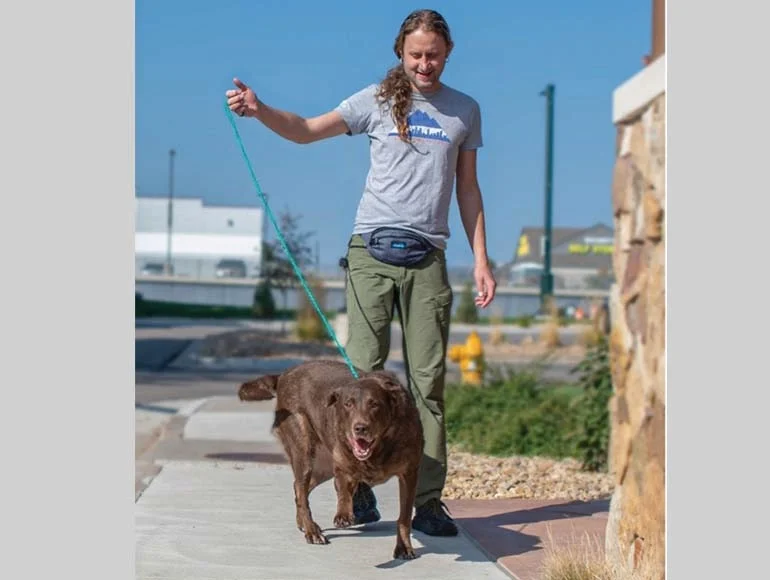

To correct for this “shelter effect” and gain a more accurate picture of a dog’s temperament, Ben tries to communicate predictability and a sense of “normalcy” during dog visits through consciously modifying his own behavior. When he first retrieves a dog from their kennel, he uses affectionate words or positive phrases that they may have heard before arriving at the shelter: “Let’s go outside!” or “Go for a walk?” usually top the list. “This can really change their mindset,” Ben says. “The dog will often correlate these phrases and my tone to a time when their previous owner was excited to see them, making them more relaxed before meeting an unfamiliar dog.”

Once in the play yard, Ben uses distraction techniques when waiting for the other dog and handler to arrive. Because dogs are so perceptive, they can sense when changes are afoot. “That unknown can build like a volcano,” he says. Applying what he calls “a light, beebop-type” movement, Ben will circle the yard to get the dog to focus on him. He also tries to keep his behavior consistent. For example, if he’s chatting with the other handler, he’ll continue to do so throughout the entire visit, keeping his tone calm even when squabbles or more serious concerns arise. “That way, the dog will see that nothing has changed with me, so there’s no reason to be concerned, no need for that volcano to erupt.”

While Ben has learned to be intentional in his behavior, there are still many things animals pick up that we can’t control. “Human behavior is constantly being interpreted by animals,” says Jes Cytron, the League’s Director of Shelter Behavior and Veterinary Services. “What we can control is our body language, tone of voice, eye contact, and [other] physical projections, but cats and dogs have incredible senses of smell and can detect our hormones, particularly the stress hormone, cortisol.” As such, Jes continually coaches teams across the organization on being thoughtful about their emotional state and how it may influence their work.

As animals transition from the shelter to a home environment, they continue to follow the lead of people in their lives. We are the people our pets look to for guidance, especially as they learn to navigate a whole new world. In fact, everything we do communicates something to our animal friends, and it is therefore up to us to be aware of our behavior so that we convey what they need most – trust, reliability, and tenderness.

We encourage people to practice. Try reflecting on your pet’s perspective or the feelings they may be experiencing. Think about the sensitivity required to communicate through non-verbal cues alone, and the confusion that may arise if your companion behaves out of character without explanation. This exercise can help us empathize with our pets and their “frustrating” behaviors, but it can also help us understand and manage ourselves so that we can be better for them. For example, your dog may be chewing on your shoe, not because they are a “bad dog,” but because your heightened tone during a tense Zoom meeting caused them stress. Taking a moment to breathe during a call like this can be helpful for you and your pet.

The more you tune into yourself, the more connected you and your pet can become. “I learn every day,” says Ben. “You never master it, but you always have new situations and animals to learn from. And I know for a fact that being aware of my own behavior has an impact.”